---oOo---

|

| Fig. 1: Humphry Repton by John Downman, c. 1790 |

On this day 196 years ago, 24th March 1818, the famous late 18th century landscape gardener Humphry Repton died. Born in 1752 in Bury St. Edmunds, Suffolk [1], Repton did not turn to ‘landscape gardening,’ a term he himself coined, until 1788 at the age of 36. [2] He proved a worthy successor to the great Georgian landscape architect Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, and Repton was very inclined to fill the gap left by Brown’s death in 1783. In consequence of his extraordinary ability and talents, despite his hitherto inexperience with horticulture, Repton became an immediate success. He received commissions from many well-known aristocrats and politicians of the age, including the then Prime Minister William Pitt the younger, and his friend, the Speaker of the House of Commons, Henry Addington (later Viscount Sidmouth, and Prime Minister between 1801-1804). Indeed, many of Repton’s clientele in the 1790s were men who were politically affiliated with Pitt [3]. This included the appointment in 1792 to work on Pitt’s brother in-law Edward James Eliot’s family seat at Port Eliot in Cornwall. [4] From these numerous commissions Repton produced ‘Red Books’ (known for the colour of their binding) which used ‘before’ and ‘after’ watercolour overlays, and explanatory text in order to help client’s visualise his projective designs. [5] In fact, the ‘Red Book’ of 1792 produced by Repton on Port Eliot was personally approved by Pitt. [6] As a result of Repton’s work, which was partially the result of Pitt’s influential patronage, a new fashionable gardening style was launched emphasising the natural characteristics of the English landscape. [7]

|

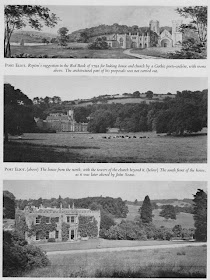

| Fig 2: Three views of Port Eliot, Cornwall, Edward Eliot’s family seat. |

When in later life, after a carriage accident in 1811 forced Repton into an early retirement, he decided to use his spare time writing his memoirs. My specific focus is to examine Repton’s personal accounts of his time consulting with two prominent politicians – William Pitt the younger at his country villa at Holwood in Kent, and Henry Addington at Woodley Lodge in Berkshire. During the time of Repton’s acquaintance with those two great men in the 1790s, Pitt was First Lord of the Treasury and Chancellor of the Exchequer, and his friend Henry Addington was Speaker of the House of Commons. Pitt and Addington had known each other from childhood, Addington’s father being Pitt’s father Lord Chatham’s family physician. As a result of this early bond they retained a close personal friendship beyond the realm of politics.

In his memoirs, Repton states that he first became indirectly acquainted with William Pitt in December 1792 through Pitt’s political friends and adherents George Rose and Charles Long, although he latterly confused the first names of the two politicians. [8] Repton had been consulted about the grounds of Pitt’s Holwood House, near Keston in Kent, after additions were made to the interior of the property. The architect John Soane had been involved from the 1780s in designing a new staircase, hall, dining room, and bedrooms at Holwood, and Repton felt these internal improvements necessitated corresponding changes to the grounds of the property [9]. Pitt was apparently in agreement. He shared his father William Pitt the Elder’s (1st Earl of Chatham) interest in architecture and gardening. Although Repton did not personally meet Pitt until the middle of 1793, probably in May or July, he had made several visits to Holwood when Pitt wasn’t present. Repton had initially been expecting a cold, obstinate man. In actuality, he found Pitt to be the exact opposite, readily acquiescing to Repton’s suggestions for the improvements even if they differed from Pitt’s own ideas.

On Pitt, Repton remembered “there was a degree of cheerfulness and lightness in his [Pitt’s] manner which no one could suppose from his natural formality and stateliness of person. I recollect he took me to a spot near the entrance gate and asked how it was possible to plant out the common, which from the narrowness of the screen and the steepness of the hill he had endeavoured to do by various means. I told him at once that it was impossible. He asked, “What is to be done then?” I answered “Sink a fence and make the entrance where there is more room. Thus the Common instead of being excluded from your grounds will appear to form a part of them.” And I added “When an enemy is too powerful to be conquered, it is better to make a friend of him if you can.” He seemed greatly amused with my remark and recalled it to my recollection a long time afterwards.” [10]

Repton relates an instance in his memoirs from the summer of 1793 when, passing through Kent, he came to Holwood one evening when Pitt was there with a large party of friends. Repton was requested by a servant to come inside, and Pitt came to him immediately. Repton felt he was intruding on the Minister’s privacy, but Pitt put him at ease, saying “Mr. Repton never think that a visit from you at Holwood can be any intrusion since I always come here to enjoy that sort of pleasure to which no man can contribute so much as yourself.” [11] Repton related that “while we continued talking, coffee was brought in, and it was settled that I should remain all night, “if I could sleep in a room like a berth on board a ship,” which was that room usually occupied by Lord Mulgrave.” [12] They then joined the large party in the dining room, and later in the evening it was proposed that they should all go outside to see the late improvements by moonlight.

It seems Pitt had a penchant for sleeping in late, though he was a playful and witty host. From that same particular visit, Repton later recalled, “next morning we were out before 8 o’clock, and his [Pitt’s] friends ridiculed his attempt at early rising as he seldom was up so soon (tho’ always in time to be at the Treasury by 11). Mr. Pitt’s conversation was always animated and interesting, but I can recall to memory only a few instances - and they are flat in the repetition tho’ at the time they seemed bright and amusing - for instance there was a dispute about the spelling of Plum pudding - and Pitt decided it was not spelt plumb with a ‘b’ and said “surely I ought to know having been made a member of the Grocer’s Company!”” [13]

Another amusing instance of Pitt’s quick repartee, which was memorable enough to be quoted by Repton twenty years later, was an anecdote regarding a conversation on the beauties of Stowe [House in Buckinghamshire]. Repton remembered, “…someone said “The Temple of Modern Friendship [sic] was a misnomer since it contained no two heads of which the originals were sufficiently friendly to sit together in the same room.” Upon which Pitt remarked “Very true - but these heads would stand by one another nevertheless on some occasions.” [14]

|

| Fig 3: An early 20th century photograph of Addington’s Woodley Lodge |

Repton continued to enjoy an advantageous access to Pitt throughout the 1790s. In 1798, he even spent time with Pitt at Woodley Lodge, the seat of Pitt’s great friend Henry Addington (later Pitt’s successor to the Premiership) at Sonning in Berkshire. This probably occurred on several occasions due to the tone of Repton’s memoirs. The visits with Pitt and Addington at Woodley Lodge can be dated to around 1798, and display the easy familiarity and privileged position Repton enjoyed. The Reading Mercury reported on 23rd July 1798 that Pitt had been on a visit that week to the Speaker’s [Addington] at his seat at Woodley. [15] Perhaps Repton was also staying there at that time. Also, in a letter from Pitt to Lord Auckland on October 22, 1798, he told Auckland that he was “…staking out my new road with Mr. Repton” [16]. On the very same day, Pitt wrote to Addington to the same effect, telling him “I borrow a few Minutes from the Instructive Conversation of our Friend Mr. Repton, (who is now here [at Holwood] and staking out an Approach).” [17] This letter, and especially the words “our Friend Mr. Repton,” indicates that by October 1798 Repton was on a friendly footing with both of them.

Above all, Repton enjoyed the brilliancy of the conversation he witnessed between Pitt and Addington. Repton later mused that “Addington excelled by being [the] most serious, and Pitt was the most quick in repartee,” and he was astonished watching Addington and Pitt swapping quotations under a large Beech tree at Woodley in Latin, Greek, French, and English! [18] Both politicians had an extraordinary memory, and a superior knowledge of the classics. However, what struck Repton most of all about the two men was their genuine fondness for each other. Writing in his memoirs many years after Pitt’s death, Repton reminisced that Pitt and Addington “loved each other as brothers, and played together like schoolboys.” [19] Pitt was always fond of children, although he never married himself, and Addington’s family was no exception. Repton poignantly described having seen Pitt playing with Addington’s children at Woodley, with Pitt “romping” around, and “rolling on the carpet or the lawn with them while the fond father [Addington] laughingly looked on with proud affection.” [20] That the eminent landscape architect shared the private intimacy of the greatest men of the Georgian period is beyond a doubt.

References:

1. Stroud, D. (1962) Humphry Repton. London: Country Life Limited, p. 15.

2. Loudon, J. C. (ed.) (1840) The Landscape Gardening and Landscape Architecture of the late Humphry Repton. London: Longman & Co., p. 114.

3. Stroud, D. (1962) Humphry Repton. London: Country Life Limited, pp. 69-70.

4. Ehrman, J. (1996) The Younger Pitt: The Consuming Struggle. London: Constable, p. 87.

5. Repton, H. (1803) Observations on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening. London: T. Bensley.

6. Stroud, D. (1962) Humphry Repton. London: Country Life Limited, pp. 69-70; Ehrman, J. (1996) The Younger Pitt: The Consuming Struggle. London: Constable, p. 87.

7. http://www.librarycompany.org/color/section5.htm. Accessed on 21 March 2014.

8. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, ff. 54-55.

9. Stroud, D. (1962) Humphry Repton. London: Country Life Limited, pp. 69.

10. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, f. 55.

11. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, ff. 56-57.

12. Ibid.

13. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, f. 57-58.

14. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, f. 58.

15. Reading Mercury, Monday 23 July 1798.

16. Auckland, R.J. E., Auckland, W.E. & Eden, W. (1862) The Journal and Correspondence of William, Lord Auckland (Volume 4). London: Richard Bentley, p. 62.

17. Sidmouth MSS. Devon Record Office. 152M/C1798/OZ/4. William Pitt to Henry Addington, Hollwood. October 22, 1798.

18. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, ff. 58-59.

19. Humphry Repton’s Memoirs. British Library Add Ms 62112, ff. 59-60.

20. Ibid.

Image Credits:

Fig. 1: Portrait of Humphry Repton, c.1790 (w/c on ivory), Downman, John (c.1750-1824) / Private Collection / Photo © Philip Mould Ltd, London / The Bridgeman Art Library.

Fig. 2: Port Eliot, Cornwall. Source: Stroud, D. (1962) Humphry Repton. London: Country Life Limited, p. 58.

Fig. 3: Woodley House, also known as Woodley Lodge, Sonning Berkshire. http://www.berkshirehistory.com/castles/woodley_lodge.html. Accessed on 21 March 2014.

Biography of the Author:

Stephenie Woolterton has an MSc in Social Research, and a background in Psychology. She is currently researching and writing her first book on the private life of William Pitt the Younger. She is also working on a historical novel about Pitt’s ‘one love story’ with Eleanor Eden.

She blogs at: www.theprivatelifeofpitt.com and can be contacted via Twitter at: www.twitter.com/anoondayeclipse.

Written content of this post copyright © Stephenie Woolterton, 2014.

Such a really great post. Thank you for including him. I haven't heard of him before now, and yet it seems like he was a major player, especially if he was Brown's "descendant" in the gardening field, if you will.

ReplyDeleteI thought of you when Stephenie told me of the topic of the post; so glad you enjoyed it!

DeleteAs this is my absolute favorite period of British history, I thoroughly enjoyed the post. I take it from the bibliography that Repton's memoirs are unpublished? There's another project for you, Stephenie (after you complete Pitt!). Your post makes me look like a total slacker in my blog posts.

ReplyDeleteI love Stephenie's work; her passion and research just shines through!

Delete